Retrieved from: https://www.gcmonline.com/latest-stories/wildflowers-golf-course-beneficial-insects

By Dr. Adam G. Dale, PhD

Incorporating flowering plants on golf courses is a well-known strategy for aiding pollinators, but the practice offers another perk: attracting predatory and parasitic insects for natural pest control.

Blooming Canada toadflax (Linaria canadensis) adjacent to the tees on one of the golf courses that allowed researchers to convert out-of-play areas to pollinator habitat. Photo by Adam Dale

In recent years, an increasing number of golf courses have repurposed out-of-play acreage to reduce irrigation, mowing, pesticide applications and other maintenance inputs that require considerable time and money. As a result, out-of-play areas have become naturalized roughs, wildflower plantings and monarch waystations, many of which are focused on conserving insect pollinators, which increasing evidence shows are declining around the globe.

This is important, because insects pollinate more than 75% of flowering plants. Although pollinator decline is caused by multiple factors, habitat loss and fewer flowering plants are part of the problem (6). Fortunately, a 2019 survey by the National Recreation and Park Association found that 95% of the American public favors designated areas that support pollinators.

Researchers like those in the lab of Dan Potter, Ph.D., at the University of Kentucky have demonstrated that wildflower habitats on golf courses can provide valuable native bee conservation while also reducing golf course maintenance inputs (4, 5). Despite this, it can be difficult to transition to a new way of creating and maintaining space on a golf course without convincing evidence that doing so provides business value. Over the past three years, my lab at the University of Florida has been working on identifying other benefits that out-of-play wildflower habitats may provide for the golf industry.

Pollinators do more than pollinate

Flowering plants attract not only bees but also predatory and parasitic insects that primarily feed on plant-feeding insects and supplement their diets with pollen and nectar. For example, specific flowering plant species, including shrubby false buttonweed (Spermacoce verticillata), partridge pea (Chamaecrista fasciculata) and white Pentas lanceolata attract the Larra wasp (Larra bicolor), a parasite of mole crickets in the southeastern United States (1, 9). The presence of these plants increases natural control of mole crickets up to 650 feet (~198 meters) away from where they are growing (9).

A mole cricket parasitoid wasp (Larra bicolor) visits a shrubby false buttonweed (Spermacoce verticillata L.) flower. The Larra wasp parasitizes mole crickets and gets additional nutrients from flowering plants. Photo by Lyle Buss, UF IFAS Entomology

Mole crickets may not be a problem in your area, but what about white grubs or caterpillars like armyworms, webworms and cutworms? What about armadillos, raccoons, moles, skunks or birds on the hunt for six-legged protein just beneath the soil surface or in the thatch? If any of these organisms are a concern, flowering plants in out-of-play areas on the course may help.

Thread-waisted wasps (in the Sphecid family) and Tiphiid wasps are two diverse groups of insects attracted to a variety of flowering plants that also hunt white grubs that feed on turfgrass roots (10). Once a grub is found, the wasp injects it with neurotoxins and lays an egg on its paralyzed body. Still underground, the wasp egg will hatch into a larva that gradually eats the grub alive and eventually emerges from the soil as an adult wasp on the hunt for more white grubs.

Potter wasps and mason wasps (both in the subfamily Eumeninae) supplement their diets with flowers, but are common predators of caterpillar pests. These insects fly around on the hunt, snatching caterpillars out of the turf and bringing them back to feed to their offspring. Increasing the number of these wasps leads to greater caterpillar control in fairways and reduces the likelihood of caterpillar outbreaks (2).

Examples of these National Geographic-like interactions between insect predators and their prey can be fascinating, but what can they ultimately mean? A recent economic analysis found that the parasites introduced to control mole crickets have substantially reduced mole cricket populations in pastures and have saved the Florida cattle industry about $13 million per year since their introduction in the mid-1980s (8).

Golf course wildflowers: What should you plant?

The aesthetic value (color, texture, height, seasonality) of the species planted in out-of-play areas is certainly important. Just as turf species or varieties are selected based on local conditions (sun, soil, water, nutrients, salinity), wildflower species should also be selected according to the site conditions.

In addition to these standard considerations, two important aspects of wildflower habitats are flowering seasonality and the number of species planted in a mixture. When creating wildflower mixtures, select plants that maximize the time of year when at least one species is in bloom. This approach will ensure there are always flowers present to attract insect pollinators.

We also know from other research that increasing the number of plant species in an area can translate to more wildlife species. We carried out an experiment to determine whether the number of wildflower species planted affects the number of beneficial insects attracted to the area and the biological control services they provide.

The habitat being replaced also matters

Not all turfgrass areas on a course are equal when it comes to supporting beneficial insects. In addition to flowers, other plant characteristics like height or architecture can be valuable to beneficial wildlife. For example, taller turf that is mowed less frequently typically harbors more predatory ground-dwelling arthropods (spiders, beetles, ants) than lower-cut turf does (3). When choosing between a low-cut turf or a higher-cut turf, opting to replace the low-cut turf will do more to reduce maintenance costs and provide habitat for ground-dwelling beneficial insects.

Our experiment

To measure the effects of out-of-play wildflower plantings and the number of wildflower species in a planting on beneficial insects and the pest control services they provide, we created three 5,000-square-foot experimental plots on three golf courses in north-central Florida. On each course, we compared mixtures of nine wildflower species, mixtures of five wildflower species, and out-of-play maintained turfgrass. Each of our wildflower mixtures flowered to some degree from March through December (Table 1).

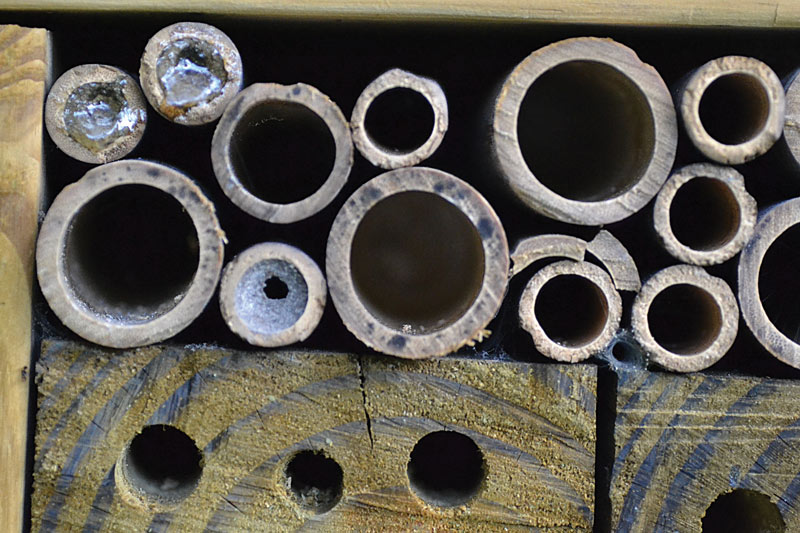

From April through October, we surveyed bees, predatory flying insects and ground-dwelling predatory insects within each plot and in the fairways adjacent to them. We also placed pollinator nesting boxes filled with bamboo reeds and hole-drilled wooden blocks in the center of each plot to provide nesting habitat for native bees.

To carry out this research, plots of wildflowers were planted on three golf courses in Florida. Each plot was 5,000 square feet. Photo by Tyler Jones, UF IFAS Communications

To measure natural pest control in the fairways adjacent to each plot, we placed fall armyworms contained in cups onto the fairways and measured how many of them were eaten by flying insects. Using these data, we can make conclusions about how the presence of wildflowers, number of wildflower species and proximity to wildflower habitats affect beneficial insects and the value they provide on golf courses.

Results

As predicted, we found that converting areas of maintained turfgrass into wildflower habitats increased the abundance of native bees and flying insect predators and parasites. An especially important result was that native bees were three to four times more abundant in the high-diversity wildflower plots (mixtures of nine species) than in the low-diversity (five or fewer flowering species) and turf plots. Similarly, the number of wildflower species affected the abundance of predatory and parasitic insects visiting them — more species equaled more beneficial insects (Figure 1).

We also frequently checked the bee hotels to see what had colonized them. Surprisingly, a predatory wasp, the red-and-black mason wasp (Pachodynerus erynnis), was nine times more abundant than any other colonizer. This wasp specifically attacks caterpillar pests like fall armyworms, sod webworms and cutworms.

Because more predatory insects does not always mean greater pest control, we attempted to determine how pests were affected by the increased number of wasps. After placing fall armyworms in the adjacent fairways, we found a 50% increase in predation from flying insect predators (those that are attracted to flowering plants) up to 60 feet (~18 meters) away from the plots. In this case, having more wildflower species led to a consistent increase, but the low-diversity wildflower plots also increased pest control (Figure 2). The presence of flowers (as few as five species in this case) led to greater insect pest control in fairways.

What lies beneath the flowers?

Pollinator habitat generally brings to mind bees and butterflies. However, a lot of beneficial activity takes place on the soil beneath the flowers. Some of the most active and effective predators (like beetles, spiders and ants) of golf course pests live on or in the soil.

Our results for this part of the study were not as straightforward, but they are significant. As mentioned above, turfgrass can be valuable habitat, but mowing height affects the organisms that live in it.

Interestingly, replacing infrequently cut bahiagrass with wildflowers reduced the abundance of ground-dwelling predatory insects. However, replacing frequently cut bermudagrass with wildflowers resulted in eight times as many ground-dwelling predators (Figure 3). It is important to note that this increase in predator abundance occurred up to 40 feet (~12 meters) away in fairways, but only when replacing low-cut, high-maintenance turf. So, yes, the habitat being replaced does matter.

Opportunities for the golf industry

Creating flowering habitats in out-of-play spaces is an opportunity to reduce maintenance inputs, enhance natural pest control and reduce insect pests in maintained turf areas on a golf course. However, there are several other ways that the creation of these areas can benefit individual courses and the golf industry.

Indian blanket (Gaillardia pulchella) is in full bloom and other wildflower species are maturing in this research plot. Note the pollinator nesting box in the center of the photo.

A close-up of nesting cavities in a pollinator nesting box in a research plot of wildflowers. Some of the cavities are inhabited. Photos by Adam Dale

One opportunity is simply installing signage near wildflower plantings that provides information about the purpose and value of such habitats on a golf course. To envision the potential impact, here are some numbers from Florida: The state has about 170,000 golf industry employees and 5 million individual golfers who, combined, play over 60 million rounds of golf in Florida annually. Imagine the potential impact on club members, tourists and society if Florida courses alone enhanced environmental stewardship and engaged the public in the process.

For another perspective, think about kids who grow up in cities (where concrete outstrips vegetation and 80% of Americans — or more than 50% of global citizens — live), who have limited exposure to nature. Research in Australia found that golf courses supported more insect biodiversity than other common urban green spaces (7). So, superintendents who manage courses surrounded by city should think about the impact that experiencing nature on a golf course can have on upcoming generations. GCSAA’s First Green program is one opportunity that could certainly pair well with these conservation areas.

Recommendations for adding flowering plants to the golfscape

This research is not intended to provide the one and only way to create conservation plantings in out-of-play areas. Rather, this research is intended to begin providing evidence-based recommendations for how to maximize the value of out-of-play conservation plantings for superintendents and the environment. There are many ways to incorporate flowering plants on a course. However, no matter the site, below are five key principles to consider.

1. Plant as many different species as you can. We saw distinct benefits when nine species were planted rather than five.

2. Use native flowering plants. This research and that of others has shown that native flowering plants typically provide greater conservation value than non-native species.

3. Create mixtures that maximize flowering time. In north-central Florida, our mixtures provided blooms for 10 consecutive months.

4. Some flowers are better than no flowers. Although more species and larger plantings are better, we found pollinator and pest-control benefits simply from having flowering plants.

5. Select sites strategically. Whether considering visibility, replacement of plant material or compatibility with educational programming, choose locations that meet the intended goals.

In summary, although bees play essential roles in our environment, so do predatory and parasitic insects. There is a reason we rarely see outbreaks of caterpillars, white grubs or billbugs/weevils in natural areas (although they are present). Pollinator conservation habitats set the stage for nature to get back to work. The multitude of predatory bugs, beetles, wasps, flies and others that are attracted to flowering plants conduct daily pest control. Creating flowering habitats in out-of-play spaces increases the abundance of these beneficial organisms as well as the natural services and the educational opportunities they provide.

Funding

This research was supported by the Seven Rivers and Everglades chapters of the Florida GCSA; Syngenta’s Operation Pollinator program; and the University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences.

Acknowledgments

This research was originally published as “Floral abundance and richness drive beneficial arthropod conservation and biological control on golf courses” by Adam G. Dale, Rebecca L. Perry, Grace C. Cope and Nicole D. Benda. Urban Ecosystems. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11252-019-00907-0

I sincerely thank golf course superintendents Andrew Jorgensen, Paul Hamilton and Asa High for their cooperation and assistance with creating these habitats on their courses.

Resources that further explain content discussed here can be found at dalelab.org.

The research says …

- Out-of-play areas on golf courses can provide habitat for declining pollinator populations, particularly in urban areas.

- Many flowering plants attract both pollinators and predatory and parasitic insects that feed on common golf course pests such as mole crickets and white grubs.

- Native bees were three to four times more abundant in the plots with more wildflower species than in the low-diversity and turf plots on golf courses.

- Creating flowering habitats in out-of-play spaces is an opportunity to reduce maintenance inputs, enhance natural pest control, reduce insect pests in maintained turf areas and create educational opportunities on a golf course.

Literature cited

- Abraham, C.M., D.W. Held and C. Wheeler. 2010. Seasonal and diurnal activity of Larra bicolor (Hymenoptera: Crabronidae) and potential ornamental plants as nectar sources. Applied Turfgrass Science 7 (1):0. doi:10.1094/ats-2010-0312-01-rs

- Dale, A.G., R.L. Perry, G.C. Cope and N.D. Benda. 2019. Floral abundance and richness drive beneficial arthropod conservation and biological control on golf courses. Urban Ecosystems https://doi.org/10.1007/s11252-019-00907-0

- Dobbs, E.K., and D.A. Potter. 2014. Conservation biological control and pest performance in lawn turf: Does mowing height matter? Environmental Management doi:10.1007/s00267-013-0226-2

- Dobbs, E.K., and D.A. Potter. 2015. Forging natural links with golf courses for pollinator-related conservation, outreach, teaching and research. American Entomologist 61(2):116-123.

- Dobbs, E.K., and D.A. Potter. 2016. Naturalized habitat on golf courses: Source or sink for natural enemies and conservation biological control? Urban Ecosystems 19:899-914.

- Goulson, D., E. Nicholls, C. Botias and E.L. Rotheray. 2015. Bee declines driven by combined stress from parasites, pesticides, and lack of flowers. Science 347(6229):1255957. doi:10.1126/science.1255957

- Mata, L., C.G. Threlfall, N.S. Williams, A.K. Hahs, M. Malipatil, N.E. Stork and S.J. Livesley. 2017. Conserving herbivorous and predatory insects in urban green spaces. Scientific Reports 7:40970. doi:10.1038/srep40970

- Mhina, G.J., N.C. Leppla, M.H. Thomas and D. Solis. 2016. Cost effectiveness of biological control of invasive mole crickets in Florida pastures. Biological Control 100:108-115.

- Portman, S.L., J.H., Frank, R. McSorley and N.C. Leppla. 2010. Nectar-seeking and host-seeking by Larra bicolor (Hymenoptera: Crabronidae), a parasitoid of Scapteriscus mole crickets (Orthoptera: Gryllotalpidae). Environmental Entomology 39(3):939-943. doi:10.1603/EN09268

- Tooker, J., and L. Hanks. 2000. Flowering plant hosts of adult Hymenopteran parasitoids of Central Illinois. Annals of the Entomological Society of America 93:580-588.

Adam Dale is an assistant professor in the Entomology and Nematology Department at the University of Florida in Gainesville, Fla.